Fear and Loathing in Ísafjörður – Chapter 10

We were somewhere around Staður on the edge of the stone desert when the tiredness began to take hold. I remember saying something like “the road isn’t that bad; I can drive all the way…” And suddenly there was a terrible crash when we took a bump in the gravel road too fast, the front of the silver Toyota rising skywards and the rear axle crashing through the gravel. Upon landing, the car swerved from left to right, sliding on the loose brown gravel like a fat drunken ballerina on the floorboards of a pub. Kai in the seat next to me was gripping the handle of his door so tight that his knuckles were all white. I slowed down and got the car under control, wiping invisible sweat from my forehead and grinned at Kai and the two hitchhiking girls in the backseat. “Everybody alright?” Eager nodding of three heads but no responses, their lips being pressed tightly together, eyes staring at the deep icewater-filled ditches to the left and the right of the road. No point mentioning those Arctic Terns, I thought. The poor bastards will see them soon enough.

Earlier that day, we had woken up to a nice hotel breakfast and loads of Icelandic kafis. I was eager to be on the road as early as possible. Yesterdays drive had shown me that traveling on Icelandic gravel roads can be quite slow, and we had to cover 271 kilometres across the highland and around a couple of huge fjords to reach Ísafjörður, where we had an appointment with local musical mastermind Mugison. We had also agreed to take Karen and Agnes with us, two dreadlocked hitchhiker from Switzerland in their early twenties, who were touring the Westfjords. Svavar had introduced us the evening before.

We packed our stuff in the car, but before hitting the road we got a tour of the former herring factory by Claus, a German photographer who is living in Iceland and works in Hotel Djúpavík during the summer months.

The factory was built in 1934 under the name of Djúpavík Ltd., and at the time of its construction it was the biggest concrete building in Iceland and one of the biggest in Europe. Herring catches started to decline after 1944 and the factory was closed in 1968. Today, it’s a derelict hulk, three storeys high, coated with flaky white paint, but still full of life. Besides the birds nesting on the roof, it is partly used as a garage for rusting cars and ships, owned by the owner of the hotel; a workshop, an exhibition space and concert venue. There are lots of old machines, rusting and slowly falling to pieces, and some areas of the factory that we visited would have been considered dangerous and sealed off in Germany. The place is slowly decaying, but not in a bad way. The interior is mostly grey and damp, but surprisingly beautiful when you see compact blocks of sunlight shining through the half-closed shutters of a small window, cutting through the dust. It’s a longish building, and looking down the former processing hall gave me a feeling of vertigo.

After the dark factory, I was happy to drive around mountains in daylight again. We had collected the girls, said goodbye to Svavar, Claus and the other people at Djúpavík and set off. We drove the road back to Hólmavík and the witchcraft museum, where we turned onto Road Number 61, which led us over the barren and stony plateau of the Steingrimsfjardarheidi, past a partly-frozen waterfall and another ghostly hut in the middle of nowhere (Kai had to stop and take flowers, of course), down to the Ísafjord, the first of many fjords on the way to Ísafjörður. Driving past grey and brown rocks, with an enormous vista over the mountains and valleys of the Westfjords in the sunshine, we listened to Hjálmar, Icelands only reggae band, which Kai described as the “saddest reggae-band in the world”. They provided a fitting soundtrack for our tour down the mountains and towards the fjords.

Kai had visited the area before, but I dismissed his claims of endless drives around large fjords and drove on. And on and on an on, through veils of rain and fog, rounding one fjord after another; fjords filled with dark water and greenish-grey mountain walls all around and three or four waterfalls each. I felt my spirits damped more and more every time I rounded the outermost point of a fjord, only to see the road ahead snaking into another, the snow-capped bulk of the Hornstrandir-peninsula always on the horizon. I got really tired, so the crew on board of the silver sushi-box started counting sheep and looking out for seals in the seaweed-covered coves we passed, just to keep the driver occupied.

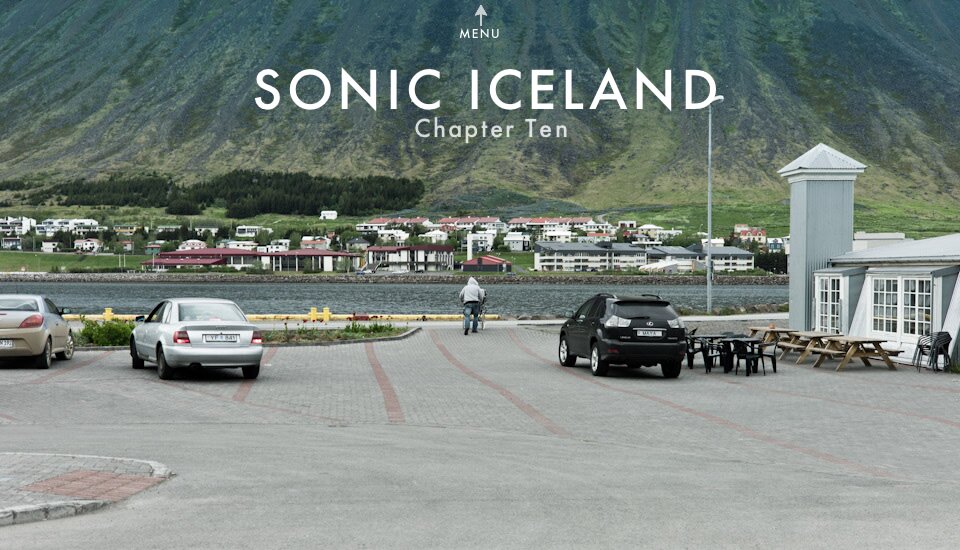

Ísafjörður looks like something that a giant child had built into the waters of the Skutulsfjord

Finally, after another eight hours behind the wheel, we arrived in Ísafjörður at the same time as a heavy shower. We had passed the small hamlet of Súðavík on the way – Mugison lives here and we had tried to reach him on the phone, but that was switched off and his small house was deserted, so we had decided to press on to Ísafjörður and find lodging for the night.

Ísafjörður looks like something that a giant child had built into the waters of the Skutulsfjord; a small colorful town with a tiny airport and a tiny harbour, inhabited by around 4,000 people, dwarfed by the steep slopes of the Tungudalur- and Engidalur-valleys all around the fjord. It reminded me of a compressed Swiss mountain resort.

Kai knew a little B&B from his stay earlier in the year, so we dropped of Agnes and Karen in the town centre (which consisted of about three shops and a pizzeria) and drove to the B&B, only to find out that the only accommodation left in town was Hotel Edda. Hotel Edda is an Icelandic hotel chain that runs hotels in schools and hospitals during the summer holidays, when there’s space and beds available. It’s an interesting concept, and the rooms are cheap (and mostly have free wi-fi), but with the smell and the looks of the place, I can definitively say that I’ve never stayed in a hotel-room before that reminded me of being prepared for an operation the next day. I was expecting a nurse to bring some pills any minute. After check-in and a short beer-shop-stop at the local vinbudjin, we finally got hold of Mugison, and we quickly drove of towards Súðavík again.

Read our interview with Mugison

On the way back to the hotel, we passed my first Hákarl, dried shark, hanging to dry in a small booth – I did not sample it, though. In town, we found out that Ísafjörður on a Monday night is not known for its debauchery. We did not find one pub, and after a hamburger-dinner in a place where we were the only guests besides a few loud Poles and one single mother, we retired to our hotel room and demolished a crate of Viking pilsener. We also found out that Karen and Agnes had pitched their tent on the grounds of the hospital, errr hotel, but they turned down our invitation to drink in our room and preferred to stay in their tent. In the rain. After a couple of beers at the hotel room I again felt the hours behind the wheel, and again fell into a deep sleep, dreaming of Arctic Tern swooping down on me.