Little Trip – Chapter 9

“Stop the car! Stop it!” I step on the brake, and the car skids to a halt on the gravel road, brown dust wafting from under the tires. Kai is out the door in an instant, unscrewing the cap of the camera lens while running towards an old church on the side of the road. But we are nowhere near an accident or bloody urban disturbance, Kai has just found another motive for a landscape image in the almost uninhibited northwest of Iceland, the Westfjords. While Kai is taking pictures of the church, I lean back into the seat and listen to the cries of the seagulls, the only sound out here besides the wind and the ticking of the motor. Kai will be back. This is not the first picture he has taken on this trip.

We were finally on the road. The day before our interview-and-drinking marathon two days ago, I had booked a rental car. Our plan was to drive to a place called Djúpavík, where singer/songwriter Svavar Knutur had invited us to attend a show. We knew about Djúpavík from Sigur Ros’ “Heima” movie, where the band played a show in the disused fish oil factory in the village. As this movie played a huge part in developing the idea for Sonic Iceland, we were eager to compare the scenes from the movie to reality. Helgi Jonsson had also provided us with the phone number of Icelandic music mastermind Mugison, who is also living in the Westfjords, so we hoped to arrange a meeting with him in his hometown Súðavík.

After an enormous hangover and a Saturday spent on the couch, we started towards the Westfjords very early on a Sunday morning. Our silver Toyota was packed with CD’s, cookies and an extra petrol can. The first thing the rental company did was to send me a guide to driving on Icelandic roads, and a spare petrol can was highly recommended. It seemed petrol stations were not as numerous as in mainland Europe. The spirit on board was however extraordinary: we were finally leaving the concrete surroundings of Reykjavik behind, to get a glimpse of the wilderness that form the backbone to all the stereotypes people had when thinking about Iceland.

We left Reykjavik, drove past Mosfellsbær and around the flanks of Mount Esja dropping off into the Kollafjord, skipped the tunnel to Akranes and rounded the Hvalfjord on the way to Borgarnes. We had started in Reykjavik with sunshine, but the further we drove up north the darker the sky and the mountains next to the ring road became. Driving on the motorway-like ring road was good, there were plenty of other cars on the road and we drove through a couple of villages that looked like a suburb of Reykjavik, all concrete and conjugated iron, red and blue. We stopped for a short break in Borgarnes, and the cloud-covered Mount Hafnarfjall again reminded me of Ireland, of Ben Bulben broodingly watching Sligo through a veil of rain. From there the ring road brought us to a place called Brú, where a proper motorway service area complete with hot dog-stand not only provided lunch, but also made me question the driving advices I had received. I would soon realise the value of those advices.

After Brú, we left the ring road and drove up country road number 61, encountering gravel roads for the first time. Gravel roads are common in Iceland, and much better suiting the cold winters than tarmac. The last time I had driven on gravel roads was a couple of years ago, but this road was wide enough and I felt no inclination to speeding anyway. Driving along the shoreline of the Hrutafjord, we got a first glimpse of the openness of the Icelandic country: beneath a dark roof of clouds, seagulls and arctic terns were gliding through the air over the opaque waters of the broad fjord opening into the North Atlantic. It was here that Kai made me stop for photos for the first time. He did not stop taking pictures until we went to sleep that night.

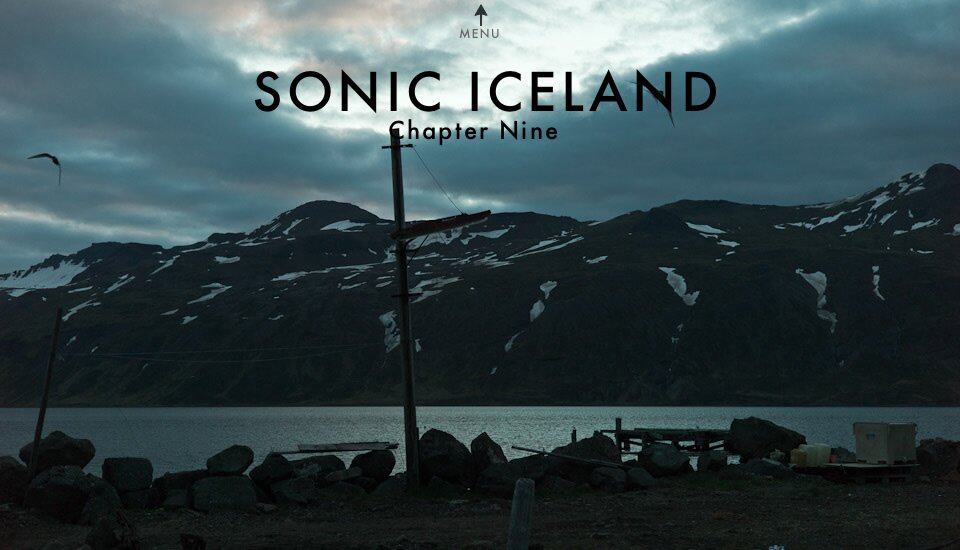

Driving along the shoreline of the Hrutafjord, we got a first glimpse of the openness of the Icelandic country: beneath a dark roof of clouds, seagulls and arctic terns were gliding through the air over the opaque waters of the broad fjord opening into the North Atlantic.

Around three in the afternoon we reached Hólmavík, a small village that I had chosen for a stopover for one thing: the Necropants. Hólmavík has a witchcraft museum, documenting centuries of Icelandic belief in witchcraft and satanism, and the Westfjords have always been a haunting ground for witches and warlocks. The museum sits in a long shed right next to the harbour, and has a couple of interesting artefacts, including the Necropants: the dried skin of the legs and feet of a dead body, enabling the magician who wears it to draw endless amounts of gold from the undead trousers. The one specimen in Hólmavík also still had a very dry and crumbled penis attached to it, and I couldn’t decide if it looked like a Halloween-prop or was the real thing. After our visit we were served a coffee by museum collector who also worked as a waiter in the attached cafe and set off soon afterwards.

After Hólmavík, the roads got worse. Smaller, more loose gravel. The tail of the car started swerving left and right whenever I rounded a bend in the road, and opposing traffic involved slowing down and biting my lips. Our average speed dropped significantly. We nevertheless managed a stop at the so-called Grimsey Trolls, three rock formations right at the shore opposite the island of Grimsey, allegedly being three trolls that were turned to stone by the sun while digging a trench towards the island. Driving on, we no longer encountered other cars, and the only houses were lonely farms and deserted holiday homes.

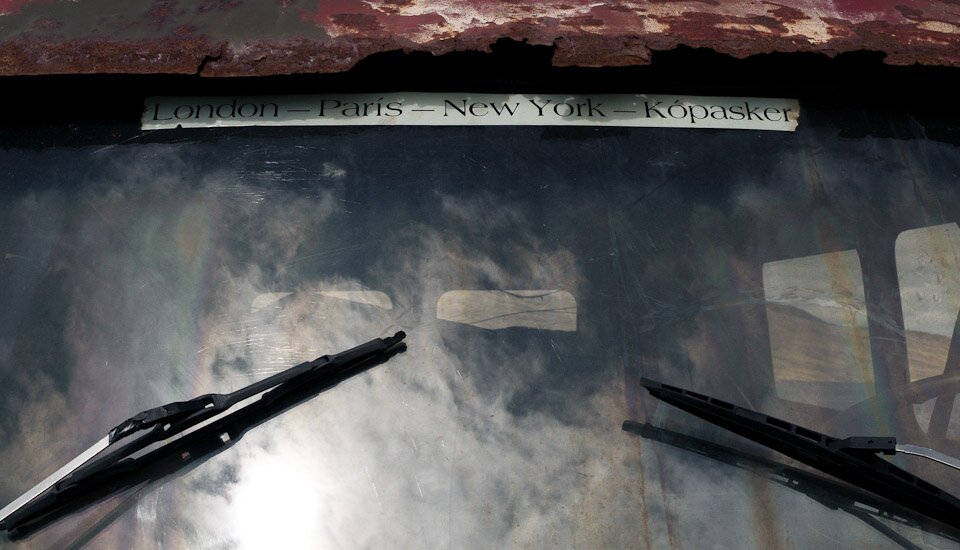

In another deserted fjord, Kai made me stop again. There was a little shed and what looked like an old van sitting right next to the water, and Kai has a thing for photographing a) crumbled ruins and b) old cars. I decided to stay in the car first, as Kai was normally quite quick, but this time he wandered off further and further, so I locked the car and followed him, filming the scenery with our little digital video-camera. The whole thing looked eerie. Walking towards the shed, I could see that it was made of conjugated iron with a flaked red roof, but completely barred up with no apparent function. No nets were hung to dry near it, no rusting machinery was to be seen anywhere, only bleached-out driftwood lying around. The smell in the place was a mixture between drying seaweed, rotting fishes and dried wood, and the only sound I could hear was the ever-present blowing wind and the cries of seagulls above us. I followed Kai along an old fence towards the van, and felt increasingly worried. Not that I was expecting some maniac with a chainsaw and leather apron to burst from the shed any moment, but being in this fjord, encircled by green-grayish mountain walls on both sides, with no apparent reason for both house and van to be there, gave me a feeling of imprisonment that was completely contradictory to the wideness of the landscape. Kai had reached the van and was taking pictures. The van looked like the shed, a rusting hulk propped up by two pieces of wood and the windows barred with wooden planks (who would do that?). Before that, I thought I heard Kai shout out in surprise, but that may have been the wind. Coming closer, Kai called over to me: “Watch out! On the ground!” On the ground, only a meter in front of me lay the carcass of a sheep, and I may have stepped in it, filming the van. “They are everywhere,” Kai said. “Gave me quite a shock.” And he was right. There were dead sheep strewn around the place, not only one or two, which I would expect in a place where sheep roam freely, but between 10 and 20 corpses lay there, all in various states of decay. Some just bones and dry skin, others still bloody with the entrails hanging out and full of maggots. Some of the dead sheep looking as if torn apart by predators and I recalled reading that Iceland has no bigger beasts of prey than cats… We left in hurry, and were happy to be back in the safety of our warm car, Apparat Organ Quartet on the stereo and leaving the fjord with the house and the car and the dead sheep quickly behind us.

There were dead sheep strewn around the place, not only one or two, which I would expect in a place where sheep roam freely, but between 10 and 20 corpses lay there, all in various states of decay.

A couple of hours later and after endless bends around 50-metre cliffs on the one side and crumbling mountain flanks on the other, we finally reached the little village of Djúpavík, which did not look like much: the crumbling hulk of the former factory dominated a few colourful houses, a small harbour and the hotel, the former quarters of the female workers of the factory. The surroundings however even dwarfed the factory buildings: there was snow visible on the greenish-grey mountain flanks left and right of the village, and a waterfall fell down almost vertically, right behind the hotel.

After a dinner of soup and local speciality salt fish, we watched Svavar Knútur play a small show with blues-diva Kristjana Stefánsdóttir from Reykjavik. Both perform together regularly in an acoustic setting, playing covers and singing own songs. Svavar had wryly warned us before, but listening to a set of Abba-covers together with (mostly German) tourists and a handful of locals, while outside the summer-sun was reflecting on the waters of the fjord, felt extremely surreal. But maybe this was just the eight hour-drive and the three beers I drank during the show.

After the show, Svavar gave us a very private tour of the place and the factory, including an improvised didgeridoo-performance inside a former tank for fish-oil. Svavar often comes to Djúpavík, which he uses as some kind of refuge for himself – he even recorded with his band Hraun inside the tank, and also plays in the hotel and the factory regularly. We concluded our evening with an Icelandic coffee at 11.30 p.m. and still fell asleep within minutes.